Advertisement: Battle of Patapsco Neck. Andrew Duluc

On the evening of September 12, 1814, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochran wrote to Colonel Arthur Brooke with the news that General Robert Ross was struck and killed at the Battle of North Point:

1/2 past Seven Monday Evening [12 September 1814]

Dear Sir

The Sad Accounts of the death of General Ross has Just reached Me— I had written him a few Minutes before by the boats in Bear Creek with a Bird’s Eye View of the fortifications of Baltimore and the New entrenchments I saw them throwing up to the NNE.—of the Town, upon Which a Good Many people are Engaged— It Struck Me that this entrenched Camp may be turned.

Since writing the before going my letter to my poor departed friend is returned. I therefore Send it to you in its Original form—

It is proper for me to Mention to You, that a System of Retaliation was to be proceeded Upon—in Consequence of the Barbarities Committed in Canada—and that if Genl. Ross had Seen the Second letter from Sir George Prevost—he would have destroyed Washington and George Town— Their Nature are perfectly known to Rear Admiral Cockburn and I believe Mr. Evans— In them a kind of Latitude is given for raising Contribution instead of destruction but in this public property Cannot be Compromised.

You will best be able to Judge what can be attempted—but let me know your determination as Soon as possible that I may Act Accordingly

Ever my dear Sir

Yours Sincerely

Alexr Cochrane

The transcript of this letter is re-posted from the Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum and Blog of 1812.

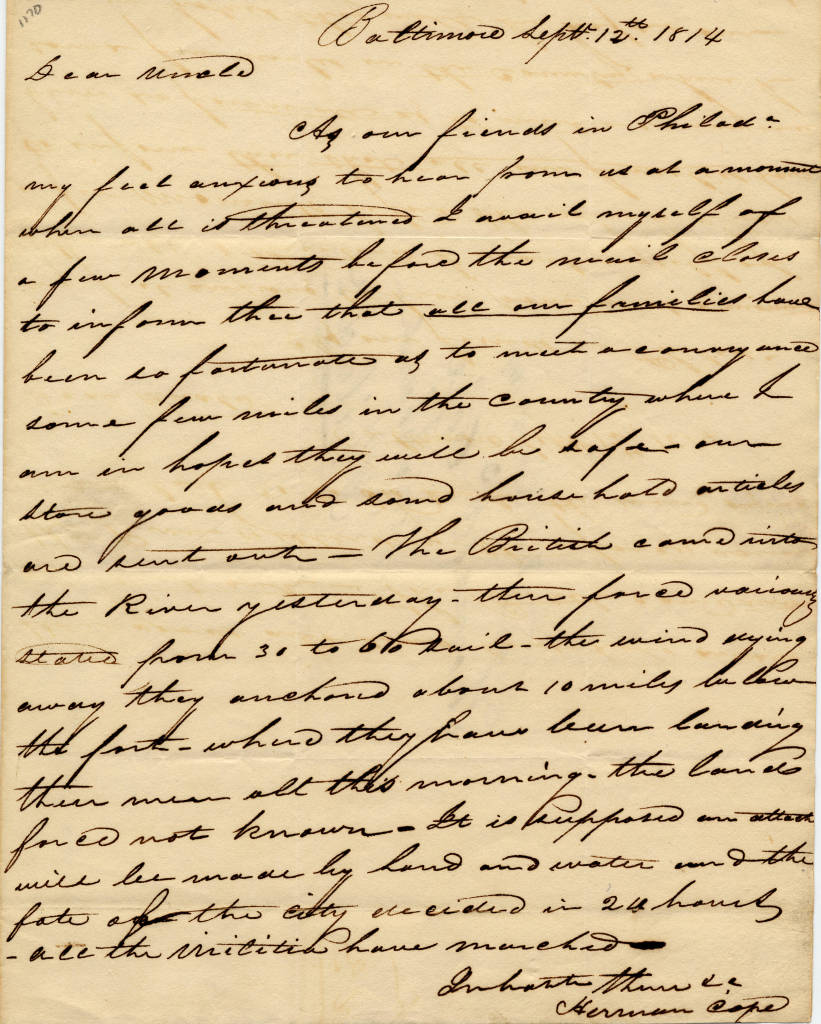

On September 12, 1814, Herman Cope, a merchant at 76 Sharp Street, wrote to his Uncle in Philadelphia and shared the news that his family had fled the city:

As our friends in Philada may feel anxious to hear from us at a moment when all is threatened I avail myself of a few moments before the mail closes to inform thee that all our families have been so fortunate as to meet a conveyance some few miles in the country where I am in hopes they will be safe – our store goods and some household articles are sent out – The British came into the River yesterday – their forces variously … from 30 to 60 sail – the wind … away they anchored about 10 miles … the fort – where they have been landing their men all this morning- the lands force not known. It is supposed an attack will be made by land and water and the fate of the city decided In 24 hours – all the militia have marched.

In haste [then] &c.

Herman Cope

In January, Herman Cope had hoped for peace with Britain in time to import dry-goods to sell in the fall. Clearly his hopes had not been realized.

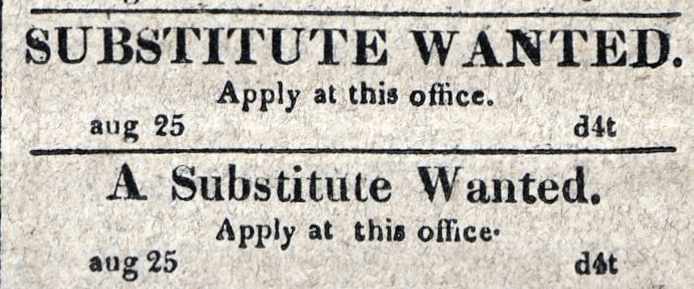

American Commercial and Daily Advertiser, August 25, 1814. Maryland State Archives, SC3392.

American Commercial and Daily Advertiser, August 25, 1814. Maryland State Archives, SC3392.

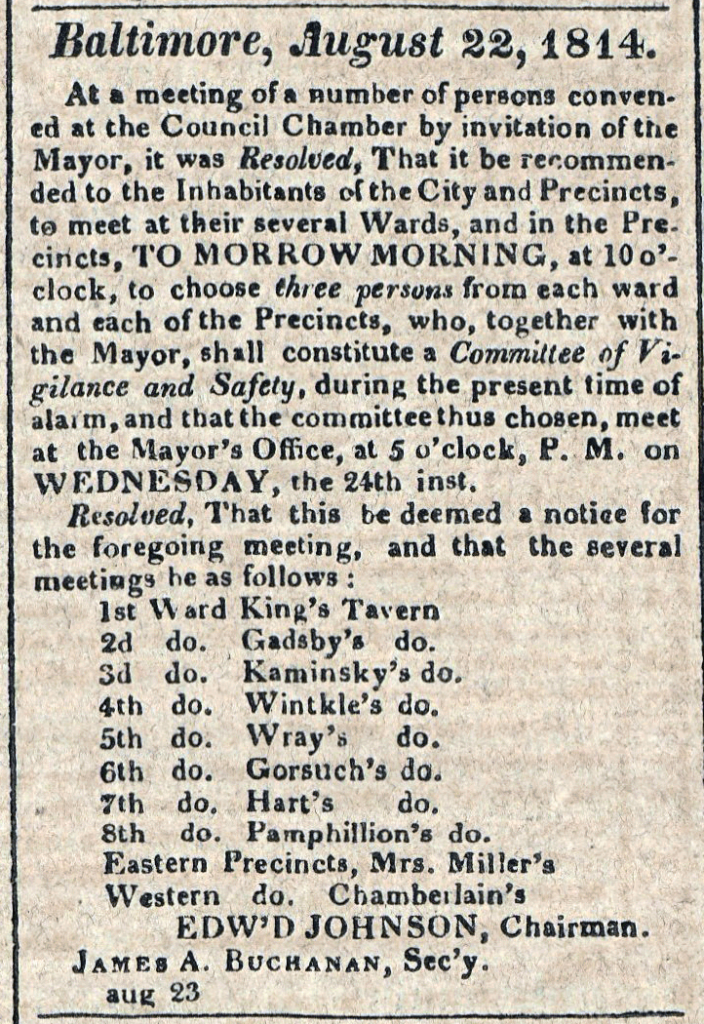

On the evening of August 24, 1814, residents of Baltimore noticed an unusual glow in the sky to the south. Historian Neil H. Swanson captured the scene in The Perilous Fight, an exceptional account of the Battle of Baltimore:

“The first stain of fire crept up into the sky along toward half past nine. It was no brighter, then, than an afterglow of the hot summer sunset. There were arguments about it. Nine and a half o’clock was late for afterglow, but what else could it be? There’s nothing over there put the Patapsco River; you can’t burn river. All it means that tomorrow will be another scorcher.

The glare increased. The arguments died down. By half past eleven there was no doubt left. A wave of fire more furious than those before it surged into the sky. It beat against the piled-up storm clouds the clouds right as if the wind was in them. From the Bal’more rooftops or even from John Eager Howard’s hilltop beyond the north end of town, a man couldn’t tell for certain which part was smoking which was thunderheads.”

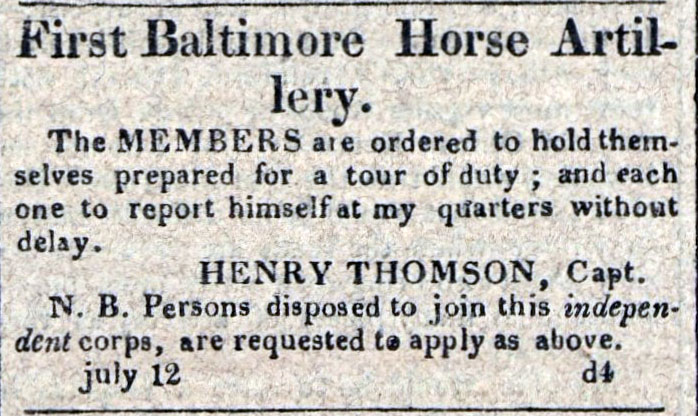

Letters from Bladensburg had started to arrive in the afternoon. Riders from Captain Henry Thompson’s First Baltimore Horse Artillery operated a horse-telegraph line along the Washington and Baltimore turnpike, with relay riders racing letters north to General John Stricker in Baltimore. James Carroll, Jr., a member of the Maryland militia, and resident of Mt. Clare in today’s Carroll Park arrived at McCoy’s tavern just after midnight with a confirmation of the terrible news:

Aug. 25th. 1814

McCoys Tavern ½ after 12 o’Clock

Thursday Morning.I left Vanhorns about 8 o’clock when on the Road to McCoys Tavern an hour after I heard two or three heavy Explosions, it was considered by the Company with me as a Renewal of the Engagement but in a little Time a Light appeared in the Horizon in the Direction of the City of Washington which encreased until the Smoke and Flame were distinctly seen this Light continues to encrease to the present Hour & I have no doubt but that the British are burning the public Buildings at Washington.

James Carroll

From the report of several Horseman come in during the night who left our party after the defeat at Bladensburg, it seems they fled mostly on the Montgomery road some stragglers of our army are progressing this way.

R. Patterson

12 ½ o’Clock

Brig. Gen. Stricker, Baltimore

While visiting neighbors on Wonton Creek in Kent County, Lieutenant Colonel Philip Reed, 21st Regiment, saw four British landing barges from the frigate HMS Loire and schooner HMS St. Lawrence. Reed quickly borrowed a musket and gathered twenty-nine neighbors armed with duck guns and muskets to ambush the British barges as they passed.

Learn more from Maryland in the War of 1812 by historian Scott Sheads.

On July 4, 1814, the American and Commercial Daily Advertiser continued its’ “annual custom” publishing the Declaration of Independence in full:

For newspaper editor William Pechin, reading Thomas Jefferson’s words held special meaning in the summer of 1814:

We have this day, according to annual custom, inserted the Declaration of American Independence.—Never since the 4th day of July 1776, has its publication become more necessary, for never since the Revolutionary war has our Independence been in greater danger from the same ambitious and powerful enemy.—Let every American read it with solemn attention, and firmly resolve, with an honest ear, and a resolute hand, to support the liberties of the Republic.

The threat of the British attacks on towns and small farms around the Chesapeake still did not prevent Baltimore from celebrating the occasion. After the holiday passed, the American Commercial and Daily Advertiser summarized the events of the day in their next issue on July 6:

“Monday last, being the annual recurrence of that memorable transaction which took place on the 4th day of July 1776, and which, we trust, for ever separated the Western from the trammels of the Eastern hemisphere, the same was observed in this city by the various Military Corps and Associations—In the morning, they parade in Market-street, from whence they marched to Pratt-street Avenue, and fired three rounds in the honor of the day—After which they returned to Market-street, when the corps proceeded to their separate parades, and dismissed, each man to his place of abode, where, we hope, they will see many happy returns of the day, and long enjoy peace and independence, the invaluable inheritance of FREEMEN, both individually and nationally.”

Others gathered for private parties, including at Rutter’s Spring where William Pechin, writing on July 7, praised their restraint:

“A small part convened at this delightful spot to celebrate the Anniversary of Independence. Fully sensible, that the memory of Freedom is too often abused by inebriated riot, this little band of patriots mingled their bowl with temperance and discretion, and after dining and drinking the following toasts, went to their respective homes with gladdened hearts and steady heads.”

The group still shared a twenty-six toasts including a toast to the City of Baltimore calling it “The scourge of traitors, the heart of oak, too tough to be split by the influence which flows through the ‘Common Sewer’.”

Happy 4th of July!

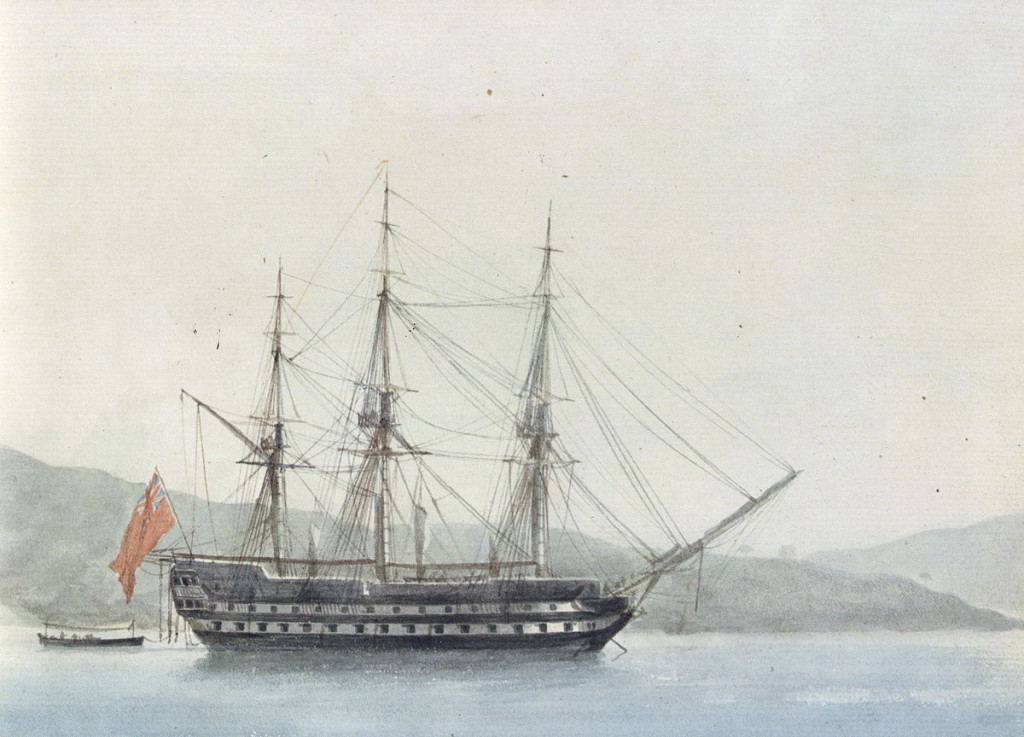

On May 30, 1814, Rear Admiral George Cockburn wrote to Captain Robert Barrie on board the HMS Dragon with news that the Chesapeake Flotilla was headed down the Bay towards the Potomac. Cockburn asked Barrie to search for the Flotilla and, if he couldn’t find it, to instead “do any Mischief on either Side of the Potomac which you may find within your Power.”

30 May 1814

My dear Sir

Subsequent to our Conversation of last Night I have received Intelligence that Commodore Barney has again come down with his Flotilla to the Neighbourhood of the Potomac.

The Man who brings the Information states that he saw him the Day before yesterday a few Miles to the Northward of the Cape Lookout— I therefore send You the Auxiliary Force I before intended, but I must beg of you to make use of it to the Northward instead of the Southward by sending it with your own Boats, Tender & ca. to examine St. Jerome’s Creek & to the Patuxent, and covering them at such Distance as you may judge advisable with the Dragon, taking also to your Assistance the St. Lawrence if on communicating with her Commander you find so employing her will not be likely to clash with Promises or Arrangements made with the Blacks landed from her the other Day.

Should you neither gain Information nor see anything of the American Flotilla in or on this Side of the Patuxent, I would have you cause St. Mary’s & Yeucomoco to be looked into, & you may do any Mischief on either Side of the Potomac which you may find within your Power, if this Information which I have received turn out to be incorrect, I can only say in your Operations to the Northward of Point Look out or to the Westward of it, You will consider yourself at full Liberty to act as Circumstances may point out to You as being most advisable for the Service.

The high Confidence I have in your Zeal and Abilities assuring me that I cannot do better than Point out to You the Object, and leave the Rest to your Management, but should you not be able to annoy the Enemy in that Direction we will still hold in View our intended Attack on Cherrystone Creek and perhaps a further Attempt on the other Side opposite to it. The Jaseur has taken another Schooner loaded with Salt Fish, she is gone up to the upper Part of the Bay near Hooper’s Straights— What Capt. Watts has in View I know not.

Let me hear from you as occasion may offer. I am Dr. Sir With much Truth

Yours most faithfully

G. C.-

This letter is cross-posted from the Blog of 1812 courtesy the Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum.