Image Archives

Advertisement: Lost, Thomas Tenant’s Note

Joseph Sterett (1773-1821) was a wealthy land-owner, merchant and planter who commanded the Fifth Regiment of Maryland militia at the Battle of Bladensburg and Battle of North Point. Thomas Tenant (1769–1836 was a Federalist, a Baltimore merchant, shipowner, wharf owner, and prize agent who served as a major in the Sixth Regiment of the Maryland militia.

How did Sterett lose a $2500 check from Tenant? Share your theories in the comments!

Advertisement: Rumour upon Rumour or one good chance for speculation Yet left.

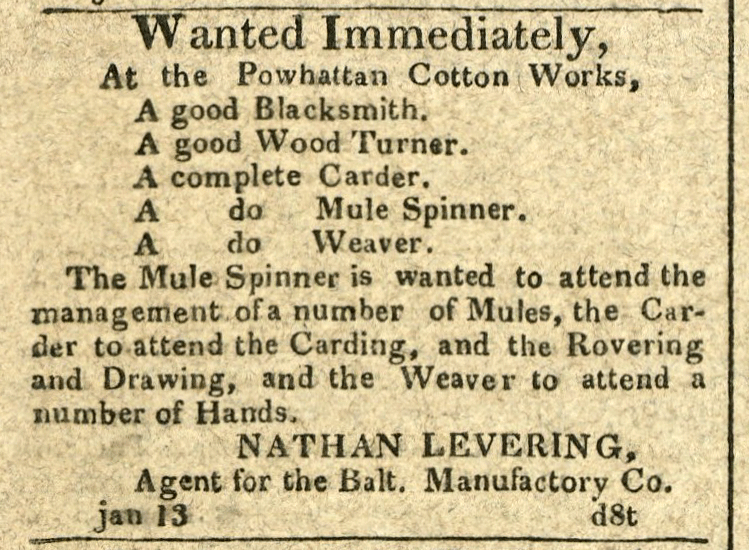

Advertisement: Wanted Immediately At the Powhattan Cotton Works

Advertisement: For Sale… the Privateer Schooner Chasseur, now ready to sail

On January 13, 1814, Thomas Kemp advertised the “Privateer Schooner Chasseur” for sale and Captain William Wade prepared to take the ship out on its first cruise. Built by Thomas Kemp for local merchant William Hollins, the Chassuer launched on December 12, 1812 but failed miserably in two attempts to evade the British blockade of the Chesapeake on commercial ventures with the second trip ending in mutiny.

Captain William Wade took command in February 1813 after the ship received a privateer commission and brought recent experience privateering as a second officer on the Comet under Captain Thomas Boyle. The Chasseur weighed almost twice as much as the Comet (resting in Puetro Rico after a damaging fight with the Hibernia just days earlier) and already had a reputation as one of the fastest top sail schooners built to date. Even with Wade’s experience and the ship’s speed, getting past the British might be a difficult task.

12 at Midnight; The Hibernia Attempting to Run the Comet Down

On January 11, 1814 at half-past midnight, the British ship Hibernia fought desperately against an attack by The Comet. Over a year before, in December 1813, the 187-ton Baltimore-built Comet slipped past a British blockade of the Chesapeake Bay and sailed south towards the Caribbean. The ship’s captain, Thomas Boyle, carried a letter of marque from President James Madison—one of five hundred letters Madison issued authorizing private ships to bring the fight to British shipping across the Atlantic.

In a little over a year at sea, Boyle and his crew recorded an astonishing twenty-seven prizes. They were on their way back to Baltimore when the ship spotted and engaged the 800-ton Hibernia in the early afternoon of January 10. After hours of maneuvers and exchanges of cannon fire that continued into the morning hours of January 11, both ships were badly damaged.

Contradictory accounts of the conflict do leave some room for interpretation. British sources, including excerpts from the British ship’s log, suggest the Hibernia was disabled, with only six cannons and a skeleton crew but still managed to kill twenty of Boyle’s crew in a desperate defense. Popular American sources describe the Hibernia differently—a formidable opponent with twenty-two guns and a full crew that left the Comet badly despite Boyle’s brave assault.

The battle ended inconclusively before dawn. The Comet retreated to Puerto Rico for repairs before finally returning home in Baltimore on March 17.

Advertisement: Attention. All persons owning ground on Oakum Bay…

In 1783, Maryland established the “Wardens of the Port of Baltimore” to oversee the construction of wharves, to help maintain clear waterways, and collect duties from vessels entering and leaving the Port. By the early 1800s, the marshy cove at the bottom of the Jones Falls — also known as Oakum Bay for the a tarred fiber “oakum” used in caulking and shipbuilding — posed a significant public health hazard. An 1808 report on the origins of Baltimore’s frequent yellow fever epidemics pointed a finger at the cove as a “sink of putrefaction,” continuing:

“So offensive were the effluvia emanating from this source of death that it affected those who had occasion to pass it even at a considerable distance interstices.”

The January 8, 1814 public meeting advertised in the American and Commercial Daily Advertiser helped to launch an effort to eliminate this hazard by filling in the cove and build the City Dock still located near today’s proposed Harbor Point development project.

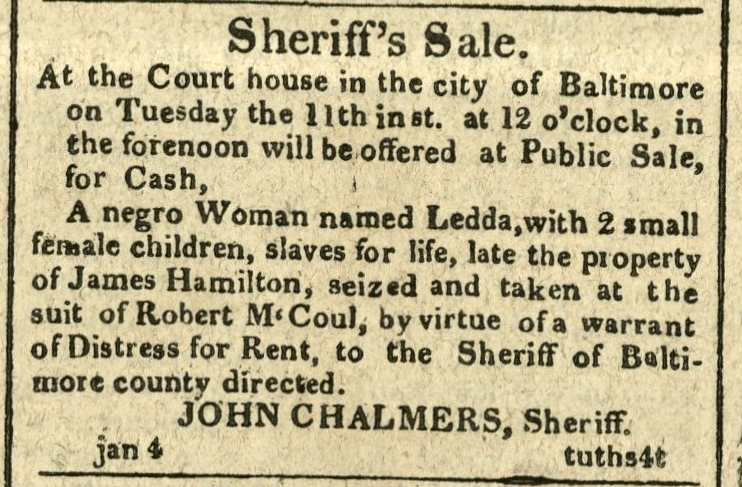

Advertisement: Sheriff’s Sale… A negro Woman named Ledda, with 2 small female children, slaves for life

Happy New Year! Welcome to Baltimore 1814

As we reflect on the past this New Year at Baltimore Heritage, we’re looking a bit farther back than usual — 200 years back. Throughout 2014, we’re sharing hundreds of stories to give you a glimpse of everyday life in 1814 — a monumental year in Baltimore’s history.

Continue reading Happy New Year! Welcome to Baltimore 1814