Fine clear day, went to Town return’d to dinner. Therm 18

From the journal of Captain Henry Thompson, February 3, 1814. Courtesy the Friends of Clifton.

Fine clear day, went to Town return’d to dinner. Therm 18

From the journal of Captain Henry Thompson, February 3, 1814. Courtesy the Friends of Clifton.

2nd Light rain & mild this morning, but clear’d up at 12 O’Clock, with wind at N.W. Went to Town & aterwards Rode to Dine at Capt. Wederstrandts in company with Oliver H. Perry, the Commodore, and Capt. Chas. G. Ridgely, very pleasant ~

From the journal of Captain Henry Thompson, February 2, 1814. Courtesy the Friends of Clifton.

There is now among us a Gallant Hero, Commodore Perry! The public spirit of Baltimore seems to have awakened to the Beams of his Glory, and shone forth yesterday in a Dinner to him A Large Company, and an excellent repast, with splendid decorations for the occasion.

Letter from Lydia Hollingsworth to cousin Ruth Hollingsworth from Baltimore, February 2, 1814. Read more stories from Oliver Perry’s visit to Baltimore.

Source: Hollingsworth to Hollingsworth, 2 February 1814, Hollingsworth Letters, Ms. 1849, Maryland Historical Society. Published in “This Time of Present Alarm”: Baltimoreans Prepare for Invasion, Barbara K. Weeks, Maryland Historical Magazine, Volume 84, Fall 1989.

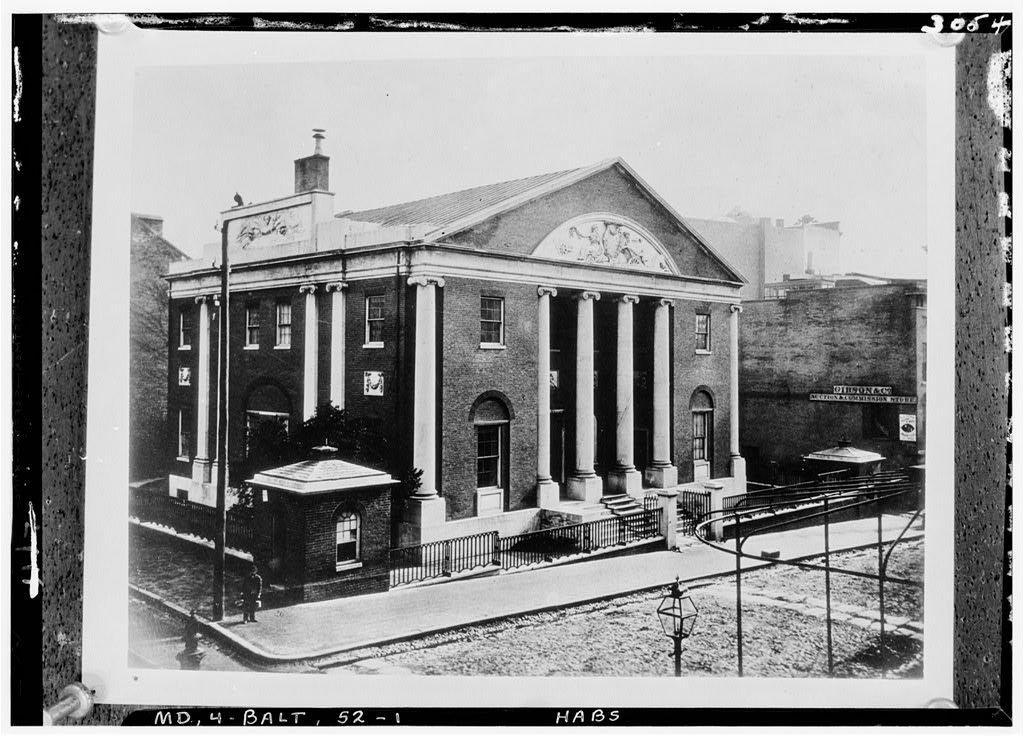

On February 2, 1814, in a letter to Reverend James Kemp, Nicholas Rogers offered up a novel metaphor for the National Union Bank (designed by Robert Cary Long at Charles and Fayette Streets) when he observed that the building was:

“wonderfully full of deformity, a sort of oyster in Architecture!”

Rev. Kemp, the recipient of Rogers’ letter and an associate rector of St. Paul’s Church, was working with Robert Cary Long on the construction of the new building for St. Paul’s Church on Charles Street.

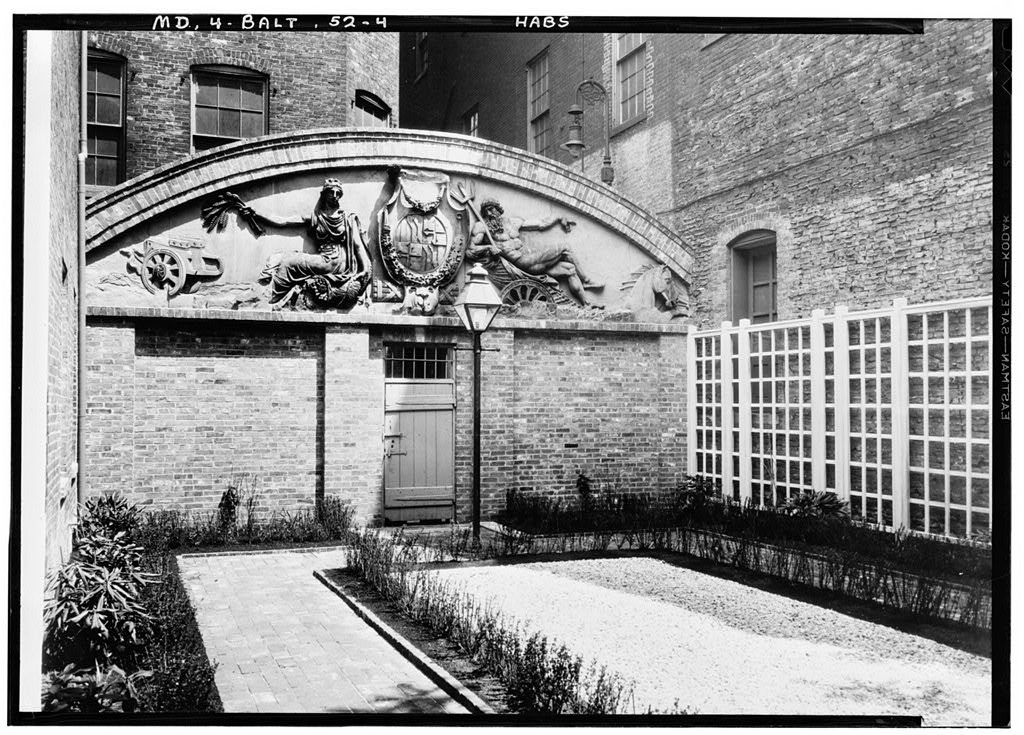

Organized and chartered in 1804, the Union Bank of Maryland was built in 1807 with architect Robert Cary Long joined by builders William Steuart and Colonel James Mosher. One artifact from the long-since demolished bank building still survives up through the present. A carved sandstone typanum, created by “Messrs. Chevalier Andrea and Franzoni,” was moved to the “Municipal Museum,” better known as the Peale Museum, where it was installed in the rear yard after the museum’s 1931 restoration.

Source: Hayward, Mary Ellen, and Frank R Shivers. 2004. The Architecture of Baltimore: An Illustrated History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

On February 2, 1814, President James Madison appointed Christopher Hughes, Jr. to serve as the “secretary of the joint mission for negotiating a treaty of peace and of commerce with Great Britian” at Ghent, Belguim. Born and raised in Baltimore, Hughes’ father was a well-known local silversmith.

Learn more about Christopher Hughes, Jr. (1786-1849) from Maryland in the War of 1812.

Source: U.S. Secretary of State James Monroe to Hughes, February 2, 1814. Christopher Hughes Papers, Clements Library, University of Michigan.

Feby. 1st – Snow this morng. Wind South, turn’d to Rain at 12 O’Clock & continued all the afternoon – Went to Town & return’d home to dinner –

From the journal of Captain Henry Thompson, February 1, 1814. Courtesy the Friends of Clifton.

Feb. 1st

Latitude 25, 29, Longitude 57, 40. Captured the British ship Galletea, from Liverpool to Pensacola, cargo hardware, how glass, white lead and claret wine; ordered her in.

From the journal of the Chasseur, excerpted in Baltimore American, June 2, 1814. Maryland Historical Society.

“31st – Very cold morning, hard Frosts – NW – Went to Town & din’d at Jas Steretts, afterward to the Circus, saw Com. Perry there.

From the journal of Captain Henry Thompson, January 31, 1814. Courtesy the Friends of Clifton.

On January 31, 1814, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, the celebrated “Hero of Lake Erie,” arrived in Baltimore from Washington, DC on his way to Newport, Rhode Island. Planning for a celebratory public dinner had been underway for weeks but on the first evening of Perry’s visit to the city, he decided to visit the circus. John Thomas Scharf paints the scene for the evening:

“That spacious building was incompetent to receive the mighty crowd that rushed to greet him. The house was crammed long before the entertainment began; and when the hero of Lake Erie entered, he was received with deep, loud and continued cheering.”

Source: Scharf, John Thomas. The Chronicles of Baltimore. Turnbull Bros., 1874. p.346.

On January 31, 1814, Herman Cope wrote to his uncle in Philadelphia in an optimistic mood. A Quaker merchant living in Baltimore at 76 Sharp Street, Cope had heard the rumors that the war with Britain might end soon, possibly “in time to admit Dry Goods from England for fall sales” and he asked his Uncle’s help in making the necessary introductions to London merchants. Business taken care of Cope turns to a more sober topic concluding:

“I suppose this you have heard that my dear Mary & myself have to lament the loss of a fine daughter in the moment of her birth – the doctors skill was unavailing – ‘The Lord giveth & He taketh away’ – Mary is pretty well – please remember me to aunt Mary Grandmother & Cousins”

Hundreds of families in Baltimore, Herman and Mary Cope among them, dealt with the death of infants and young children in 1814. Reporting in February 1814, the Niles’ Weekly Register shared some figures on Baltimore’s mortality for previous year: 249 children under the age of one died in 1814 and seventy children were stillborn.

Learn more on the history of birth in the 1700s and 1800s with the Wellcome Library’s two-part series on “Birth: a changing scene” — Part I: Images of home birth in the Wellcome Library and Part II: A controversial figure of man-midwife.

Source: Cope, Herman M., 1789-1869. “1814 January 31, Baltimore, to Uncle, Philadelphia :: Cope Evans Family Papers,” January 31, 1814. Cope – Evans family papers, 1732-1911. Haverford College Special Collections.