Advertisement: Notice. Alms House in Baltimore county… to make the appointment of Overseer and Purveyor

On April 11, 1814, Samuel Blodget, a man who symbolized the growth and ambition of celebrated in early America, died penniless at a Baltimore hospital. Born in New Hampshire in 1757, Blodget served as a Captain in the state militia during the American Revolution then became a successful merchant in Boston. He moved to Philadelphia in 1789 where he founded the Insurance Company of North America and pursued a amateur passion for architecture with a design for the First Bank of the United States (1795). Both the insurance business and the bank building have survived up through the present.

Blodget soon moved again to the new capital in Washington, DC where he successfully lobbied to win the position of superintendent of buildings and founded the city’s first bank. His once secure career began to fall apart when his mounting debts landed him in a debtor’s prison in 1802. His circumstances may have helped inspire his 1806 publication of Economica: A Statistical Manual for the United Statesnow considered the first American book on economics. The book did little to reverse his fortunes, however, and Blodget died in poverty at the age of 57.

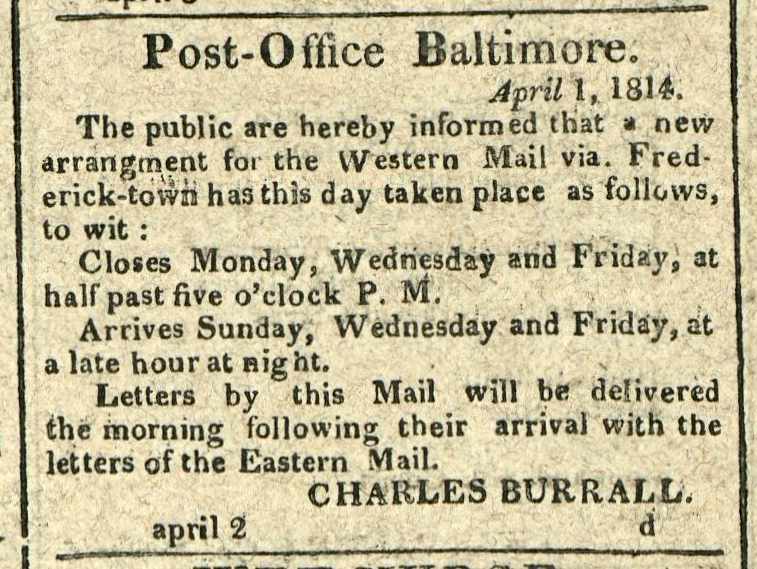

Take a look back at Charles Burral’s correspondence with Thomas Jefferson in early March.

Monticello Mar. 16. 14.

Dear Sir

Your favor of the 7th was recieved by our last mail and I have, by it’s return written to the President, bearing testimony with pleasure to the merit of your conduct and character through every stage of my acquaintance with them. no one whose conduct has been so rational and dutiful as yours ever had, or has now any cause to fear. those only who use the influence of their office to thwart & defeat the measures of the government under whom they act, are proper subjects of it’s animadversion, on the common principle that a house divided against itself must fall. you were faithful, as you ought to have been to the administration under which you were appointed, & you were so to that which succeeded it. be assured you have nothing to fear under so reasonable and just a character as the President. I am happy in having been furnished with an occasion of proving my readiness to be useful to you, and of manifesting my esteem for merit and respect for honest opinions when acted on correctly; and I pray you to accept the assurance of my friendly attachment.

Th: Jefferson

On March 16, 1814, Thomas Jefferson sent his reply to Baltimore Postmaster Charles Burrall’s letter from March 6. Jefferson’s biblical reference “a house divided against itself must fall” comes from Matthew 12.25.

Learn more about Charles Burrall and the politics around his position as Baltimore Postmaster in our original post about the correspondence.

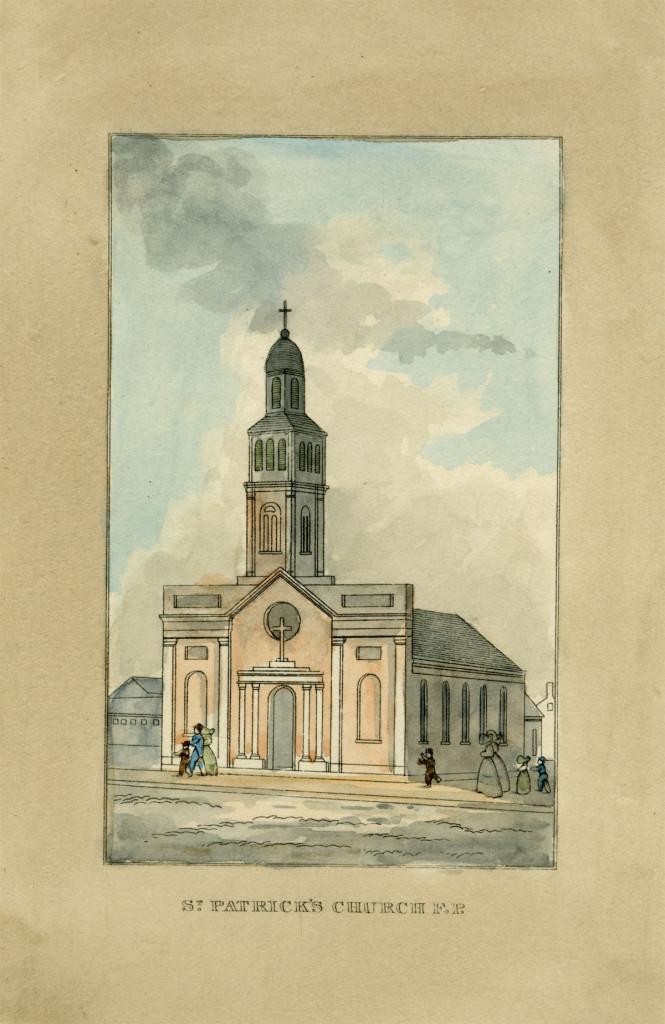

On March 17, 1814, Catholic parishioners in Fell’s Point gathered at St. Patrick’s Church in Fell’s Point to participate in a “Divine Service” led by the Archbishop of Baltimore John Carroll and Reverend Benedict Joseph Fenwick.

Archbishop Carroll (whose father Daniel Carroll had been born in Ireland) supported the St. Patrick’s Church and the city’s growing Irish Catholic community since the southeast Baltimore congregation was established in 1791. St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in the United States date to the 1760s (or earlier) and, in Baltimore, celebrations are documented as early as 1795. One account published on March 19, 1803 in the American Patriot offers a picture of the “festivity and merriment”:

“The 17th inst has been celebrated according to ancient custom, with great festivity and merriment by the sons of St. Patrick in this city. Though the Irish harp has been for some time unstrung, yet there was no lack of pipers, fiddlers and flutes on Patrick’s Day in the morning. A band of patriotic and excellent musicians paraded the principal streets, and complimented several gentlemen with airs most grateful to those who are always alive to Eire go Brath.

In the evening there was a subscription ball given at the Columbian Inn (West Baltimore Street), by some of the most respectable Irish characters in the city, when the ladies of Hibernia had an opportunity of displaying their agility and native charms.”

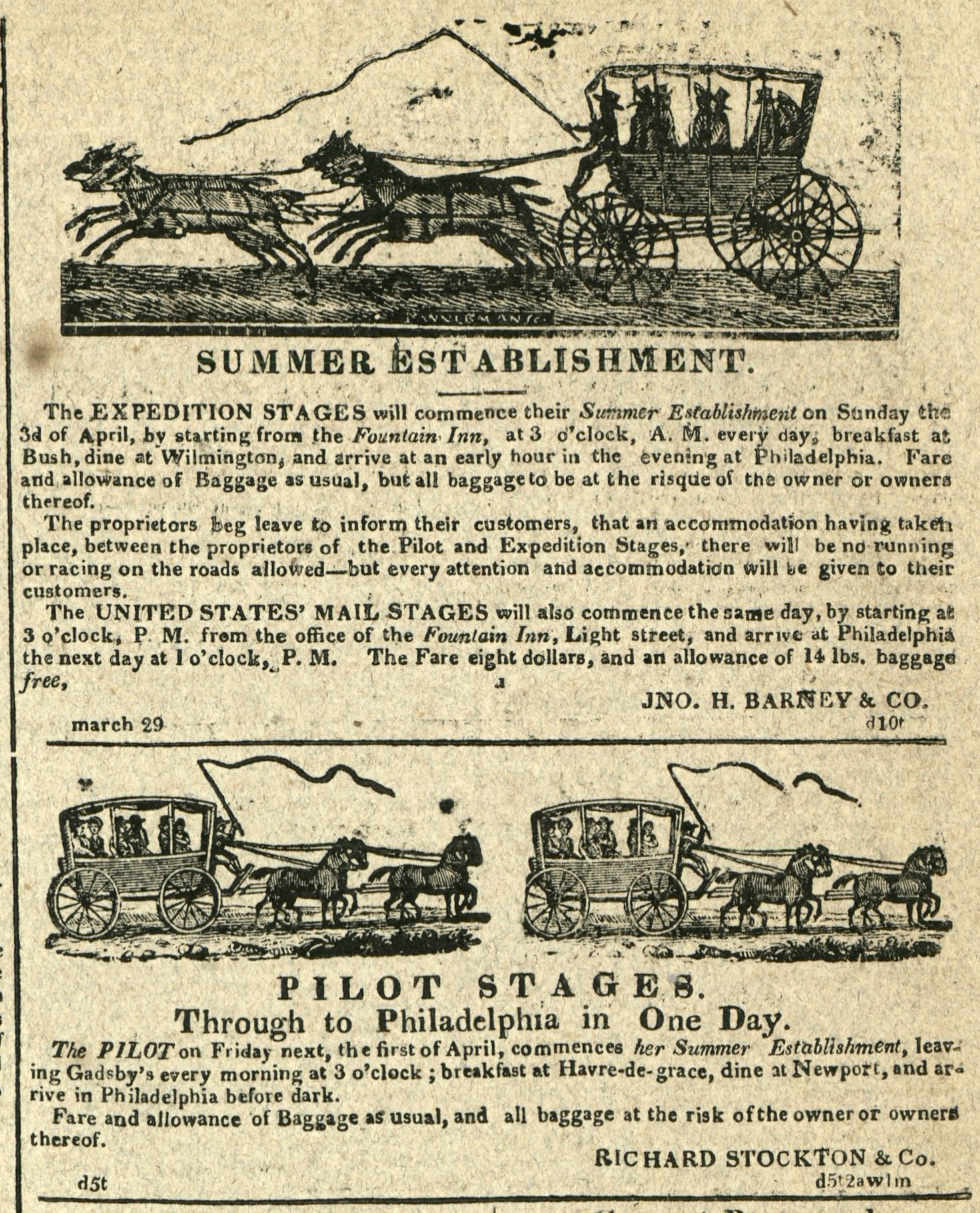

In August 1803, a group of Irish immigrants and descendants met at the Fountain Inn (then under the management of James Bryden). On August 15, 1803, the Baltimore Federal Gazette published the announcement that set out the purpose for the new group:

“Emigrants are arriving from Ireland; many of them are in a friendless and forlorn condition, deprived of health and an asylum. They have a claim upon those that have preceded them, to whom industry has proved propitious. There are many, very many of our inhabitants who feel all the influence of compassion, and who impatiently wait to be informed how they may make themselves useful to unprotected adventurers. A meeting of those who are so disposed, whether foreigners or native, is requested to morrow evening at four o’clock at Mr. Bryden’s tavern, Laight Street in order to devise a plan by which their benevolent design may be carried into execution.”

Their efforts at the Fountain Inn on Light Street soon led to the formation of the Hibernian Society of Baltimore: an Irish civic organization that continues to organize annual St. Patrick’s Day banquets and celebrations up to today.

We found no account of the Hiberian Society banquet or other 1814 celebrations beyond the morning service (historian John Daniel Crimmins speculated that the blockade of Baltimore “temporarily interrupted the Hiberian Society’s functions”) but an 1813 account of an evening dinner (published in the American on March 20, 1813) opens a window on the how the War of 1812 affected the mood of the feast day.

On March 17, 1813, a “select company of the Sons of Erin” meeting at Mr. Neale Nugent’s Tavern where they enjoyed a “sumptous dinner served up in a style of elegance” and made a series of toasts reflecting the pride of these Irish Americans in Baltimore:

The friends of reform in Ireland—May success crown their efforts—May the happiness of emancipated millions be the result of their patriotic labors.

The United States—The land of our adoption the only free country on the globe. While English drums rattle at our doors, may every friend of freedom know his place…

Our short history of St. Patrick’s Day in Baltimore 1814 is largely based on the Baltimore chapter of the 1902 history, St. Patrick’s Day: It’s Celebration in New York and Other American Places by John Daniel Crimmins. Enjoy the full chapter on Google Books for more details on St. Patrick’s Day and early Irish history in Baltimore.

Baltimore March 6, 1814.

Sir,

In consequence of the removal of Mr Granger, there will be many efforts made to remove the subordinate officers in our Dept especially where their offices are worth having, and already have individuals began to practice their insiduous arts to obtain mine—From, your personal knowledge of me, and from an opinion entertained by myself, that your sentiments have been favorable to me I have presumed Sir, to address you on this subject. …

On March 6, 1814, Baltimore Postmaster Charles Burrall wrote to Thomas Jefferson seeking his intervention in the local politics that threatened his position in the city. Born around 1763, Charles Burrall had served as a clerk at the general post office in Philadelphia in 1791, assistant postmaster general from 1792 to 1800, and as postmaster of Baltimore since 1800. Burrall knew Jefferson personally from the late 1790s when the two lived at the same Philadelphia boardinghouse.

The political attacks on Charles Burrall may have been inspired by the replacement of long-serving Postmaster General Gideon Granger but stemmed from the politics around the events of August 1812 when a local Republican mob attempted to take and destroy copies of the anti-war newspaper Federal Republican from the Baltimore post office after they arrived from Georgetown for distribution. Burrall recalled the events in his letter writing:

In the summer of 1812 I had a trying time here, and although I would not go thro’ the same scene again for any office within the gift of the President that I am capable of filling, yet I have the consolation of knowing that I then served Mr Madison with as much fidelity as I flatter myself, in your estimation, I heretofore served you—I believe I may say without vanity that I at that time contributed as much as any other individual to prevent his coming into collision with the riotously disposed of this City…

Burrall expanded on the issue and shared testimony he had delivered in court in December 1812 in a second letter sent to Thomas Jefferson the very next day:

Sir, [7 March 1814]

Since writing my letter of yesterday an insiduous piece has appeared against me in the Whig, which I enclose—It contains many unfounded suggestions to my prejudice, altho it tacitly admits that I have done my duty with correctness & impartiality…

Burrall left his position with the postal service in 1816 and took on the job of president of the Baltimore and Reister’s-Town Road Company. Burrall remained in Baltimore until at least 1824 and eventually settled in Goshen, New York where he died in 1836.

On February 14, 1814, John Merryman died in Baltimore at age 77. Born on February 16, 1736 on the 1000-acre “Hereford Farm,” Merryman moved to Baltimore Town around 1763 and built a home on Calvert Street just south of Baltimore Street.

In 1774, he helped to found the “Baltimore Town Committee of Observation,” one of many citizen groups organized around the beginning of the American Revolution to challenge the weakening authority of the British Colonial government. Merryman was commissioned as a Justice for Baltimore County in 1778 and served as a judge for the Orphan’s Court of Baltimore County in 1784. He survived by his wife Sarah Rogers Smith and four children.

Source: Browne, William Hand, and Louis Henry Dielman. 1915. Maryland Historical Magazine. Maryland Historical Society. p. 286-287.