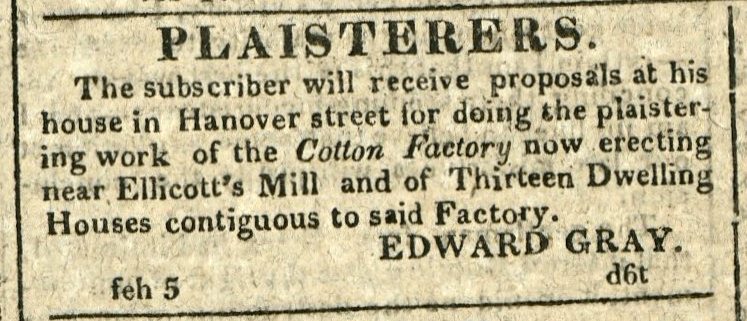

On February 5, 1814, the trustees of the Baltimore City and County Almshouse wrote to overseer John Morton, calling on him:

“to be more circumspect in his purchase of provision for the poor taking care not to have so large a proportion of bone in their meat, to have their bread attended to and well baked (particularly the indian) and to have vegetables mixed with their soup.”

While modest in some ways, the diet at the Baltimore City and County Almhouse offered greater variety and nutrition than many working people in Baltimore ate at home. Dinner included soup with an eight-ounce share of beef on Monday, Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday. Sunday inmates ate salt pork and vegetables, Tuesdays they ate mush and molasses and on Friday they ate herring with hominy or rice. Each inmate received a pound of bread daily along with a molasses-sweetened beverage of coffee and rye served for breakfast.

During warmer months than January, the almhouse menu was supplemented by produce from the almshouse farm. An 1825 harvest included cabbage, tomatoes, turnips, carrots, string beans, and onions. That same year, the almshouse cows gave 4,000 gallons of milk and cream enough for 1,735 pounds of butter.

Source: Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (2006), Seth Rockman, p.204.